Steve Richards tells the story of RAF ‘ace’ Robert Stanford Tuck…

An article kindly supplied by Steve Richards Author & Historian

Robert Stanford Tuck - One of the RAF’s highest ranking aces

Robert Stanford Tuck was one of the RAF’s highest ranking aces. By the time he was shot down and taken prisoner on 28th January 1942, he had 27+ enemy aircraft to his credit.

Tuck's Luck

His many close shaves with disaster was to give rise to the expression ‘Tuck’s Luck’. He survived two mid-air collisions, four bale outs, numerous crash-landings, was plucked out of the sea and received many relatively minor combat injuries, which apart from his ‘luck’ could so easily have been fatal.

Like a number of pilots who were later to make good, Tuck struggled as a trainee pilot, so much so that he was in real danger of being ‘washed out’. But at the last minute whilst on a make or break training flight, in the words of his instructor “…he suddenly twigged the whole thing.”

He won his pilot’s wings in August 1936, when he had just turned 20 years of age. He was posted to 65 Sqn. Whilst flying in a formation of Gladiator bi-planes, he was involved in a serious mid-air collision. This had the effect of maturing him considerably, as well as leaving him with a facial scar for life.

Action over Dunkirk

When 65 Sqn was selected as one of the first units to be equipped with the Spitfire, Tuck was chosen as the squadron’s representative to be checked out on the new type. It was a recognition of Tuck’s ability as a fighter pilot. Upon return to the squadron in January 1939 he was a Spitfire enthusiast.

By the outbreak of war 65 Sqn was operational on Spitfires, but Tuck had to wait until the Dunkirk evacuation before he saw any action and by this time he was a Flight Lieutenant with another Spitfire unit, 92 Sqn.

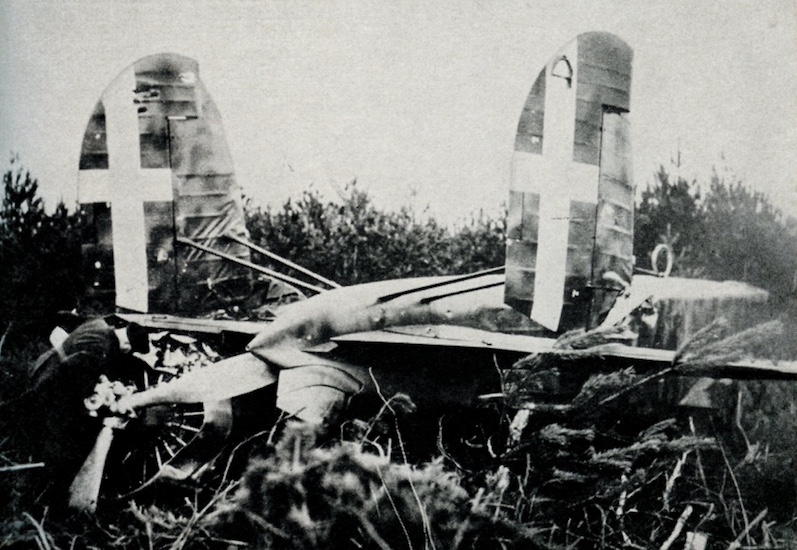

And so it was on May 23rd 1940, with the English Channel full of ships evacuating the British Expeditionary Force, Tuck found himself patrolling over Dunkirk. Whilst the pilots were concentrating on maintaining tight formation, as was current RAF practice, they were intercepted by German Bf 109Es. As one flashed over him, Tuck gave chase and, with his marksman’s eye, shot it down. He returned to the same area in the afternoon and this time tangled with a formation of Bf 110 twin engined fighters. He shot one down and gave chase to a second, with which he had almost collided. The chase went down to tree top height, the enemy trying to lose Tuck by flying beneath electricity wires. All to no avail as the enemy ended up crash-landing in a French field.

Three kills on his first day of combat!

Three kills on his first day of combat! The squadron had done well too, but lost five pilots including Squadron Leader Bushell. The next day Tuck was given temporary command of 92 Sqn and led his men back to the Dunkirk area. This time he had his pilots adopt a much looser formation. “I decided that our rigid flying tactics with formations were useless when flying against the more experienced Bf 109 pilots.” On this occasion he downed two Dornier 17 bombers and so had become an ‘ace’ in 24 hours, the first ever Spitfire ace.

Tuck & Bader - A love hate relationship

It was during these Dunkirk operations that Tuck first met Douglas Bader and immediately they irritated one another! It was a love hate relationship which was to last through their combat careers, continuing when they shared the same POW camp and at their postwar reunions.

In June 1940 Tuck had a period at Farnborough where he was a part of a team evaluating a captured Bf 109. He loved the Bf 109 flying it on many occasions, though he disliked its own peculiar smell and the poor visibility afforded by the heavily framed canopy.

Over the next weeks Tuck’s score gradually increased but much to his disgust 92 Sqn was posted to Pembrey in South Wales. So, whilst the Battle of Britain was raging over south-eastern England, he was having to content himself with intercepting the occasional recce or lone raider over the Bristol Channel. When the Battle of Britain was at its height in mid-August, 92 Sqn were often vectored to the battle zone, thus giving Tuck more combat opportunity.

“…it was like flying a brick – a great lumbering farmyard stallion.”

Then in early September came a posting to take over 257 Sqn at Martlesham Heath, Suffolk. Two disappointments awaited him. Firstly, the morale of the squadron was at rock bottom and secondly, 257 was flying Hurricanes! Having flown 1000 hours on his beloved Spitfires, his first impression on flying the Hurricane was that “…it was like flying a brick – a great lumbering farmyard stallion.” But soon he came to appreciate its great strength, having the ability to absorb punishment and the fact that it was a very steady gun platform.

Tuck arrived at 257 on September 11th and next day took up his new Hurricane which had arrived on the station a few days previously. Allocated serial number V6555, it had the standard dark earth/dark green/sky camouflage and the code DT-A. As the squadron was sponsored by funds raised in Burma, it had the Burmese flag beneath the cockpit on the starboard side. In an effort to help boost the morale of the squadron, Tuck had a long line of victory credits stencilled beneath the port side of the cockpit hood together with a cartoon representation of Churchill.

Three days later on 15th September he led his squadron over to Debden airfield to join with 17 and 73 Squadrons. On the morning he took the three squadrons on three patrols without seeing the enemy. But on the afternoon they found large German formations heading for London. The ensuing battle was fierce and Tuck again increased his score.

Later in October his Hurricane was lightly damaged and he received V6962 as a replacement. The Blitz was now in earnest and Tuck’s score increased whilst flying night patrols from their new base at North Weald, Essex.

At the end of 1940 he attended a conference to discuss the merits of equipping RAF fighters with cannon and not relying solely on the .303 machine gun. Douglas Bader was in attendance and was adamant that they should stick with what they knew. Tuck was furious! He had long cherished the day when, like the Luftwaffe, the RAF would get this lethal weapon.

The RAF did get cannon armed fighters and 257 Sqn was amongst the first to receive the cannon armed Hurricane MkIIC in Summer 1941.

Tuck was now a ‘high flyer’. In Spring 1941 he led one of the first offensive fighter sweeps over Northern Europe. By July he was promoted to Wing Commander and posted to Duxford. In October he joined a delegation to the USA, to liase with both American aircraft manufacturers and the U.S. Army Air Force. During his time in the United States, he had the opportunity to fly the Republic P43 Lancer with the 1st Pursuit Group. When he returned, he was given command of the Biggin Hill Wing. Back on Spitfires!

It was whilst flying his Spitfire Vb coded with his own initials RS-T (a Wing Commander’s privilege) that he was shot down. He was taken prisoner, but before being despatched to a POW camp, he was entertained by Adolf Galland the German ace and officers of JG26.

He escaped from the Germans in early 1945 and ended up fighting with the Russian infantry! His incredible ‘Tuck’s Luck’ held and he returned home before VE Day.

Tuck continued to serve in the RAF until 1949. Afterwards, he moved to Sandwich, Kent and became a mushroom farmer. His friendship with Galland continued over the years, as did his fiery relationship with Bader! Robert Stanford Tuck died in 1987 aged 70.

An extract from Fly for your life by Larry Forrester

What follows is an extract from Fly for your life by Larry Forrester, and refers to an incident in the second half of October 1937:

Tuck was alarmed by the number of foreign military missions courteously received by the RAF and shown ‘the works’. A party of Germans, led by German generals Ehard Milch and Ernst Udet, Great War aces – both of whom later became field marshals – had visited Hornchurch soon after 65 Sqn was equipped with Gladiators. The pilots had been warned by the station commander, Group Captain ‘Bunty’ Frew: “You can answer any questions they ask you, except about defensive tactics, operational control and the new reflector gunsight. If they get on to the gunsight, tell them it’s so new that you haven’t learned how to use it yet.”

The aircraft were lined up on the field with the pilots standing beside them, and the Germans came round to inspect accompanied by an interpreter and an Air Vice Marshal. When they reached Tuck’s aircraft, sure enough Milch got up on to the wing, stuck his head into the cockpit and inquired in passable English how the gunsight was operated. Bob stammered out the prescribed answer and the German, smiling faintly, started to turn away. But at once the Air Vice Marshal said: “Allow me, General!” – and jumped up beside him. For the next few minutes Tuck stood by, appalled, while the brass hat proudly and lucidly explained the principles and advantages of the new instrument, and even demonstrated the various settings. He was sorely tempted to suggest: “Sir – why don’t we give General Milch one to take home as a souvenir …..”

About The Author

Click to see full BMMHS event listing pages.

Contact us at info@bmmhs.org

Copyright © 2024 bmmhs.org – All Rights Reserved

Images © IWM & NAM